“I cannot count one. I know not the first letter of the alphabet. I have always been regretting that that I was not as wise as the day I was born.” Thoreau, in Walden.

I will conclude my series on fools and foolishness, not with a bang but a whimper. After all, the subject is inexhaustible. I can make no promise that we won’t be right back at it soon. In fact, just as there is a bit of Chelmite in every one of us, I’m sure there is some narishkayt in every post I write. So, rather than any pretense at wholeness or finishing flourish, I’ll write what’s on my mind now, touching on science, politics, and literacy.

Stupid Science

I met someone who was visiting from out of town. She is at the margins of academia. Her situation is precarious and must feel more so now, after the election. She is here legally, but not a citizen, and dependent on government science funding for her research job.

That job involves entering information in a database. I will be vague so she cannot be identified. She is entering geographic coordinates of biological specimens that were gathered a long time ago. She feels the work is meaningless. First, her employer is more interested in speed than in precision. “If you have to enter the geographic center of the county, just do it,” he says. And, since her work is judged partly on how many coordinates she enters per hour, she does. Second, the people who originally gathered the samples were imprecise, used a now-antiquated system for identifying species, and often relied on local guides (with all the usual cross-linguistic and cross-cultural opportunities for misunderstanding) for location names. There is no guarantee that the species name is right and that the place is right. In short, the data are sloppy.

To my surprise, I found myself defending stupid science. OK, so, the old system having been changed, it’s possible that the species is wrong on some of these records. But it’s very unlikely the genus is wrong. Something in that category was found, somewhere around there, on a day eighty (or however many) years ago. It’s one unreliable data point. And when enough such imperfect points are put together by enough people, over enough time, patterns emerge, and inferences can be made that are much more reliable than any individual observation. That’s what science is. It is a flawed, human endeavor that, in its repetition and accumulation, approaches accuracy.

Laypeople who do not understand this, who think that science is supposed to be absolutely precise and true, can make very large mistakes. For example, any particular climate science study can be challenged. All individual observations have some degree of error in them, and some could be based on incorrect assumptions and, therefore, wrong. When a study or a method is challenged, people may say, “Aha! If this is wrong, the whole thing could be wrong.” But “the whole thing” is a pattern of results across different ways of asking the question, all leading to the same conclusion. The odds of random methodological mistakes doing that are, approximately, zero.

A Letter to my Brother

“Till now democracy worked in USA. If we begin to excuse force then there is no democracy.”

This past Thanksgiving my brother brought us a couple of old letters he’d found, written from Solomon Simon to him. One was from June of 1970, the last year of my grandfather’s life, when my brother was 13. Apparently there had been an argument at a family gathering about the shootings at Kent State.

He was an ardent patriot who, though he fled Russia to avoid forced military service in the Czar’s army, had proudly served in the US Army in World War I. At the end of his life he showed absolutely no sympathy for the civil disruptions of the late sixties. For him, the mob was not an expression of the people’s will and not a source of justice, but the opposite.

In his letter, my zeide essentially blamed the protesters for rioting. In doing so, he was expressing the view of the majority of Americans at the time. But though he defended the establishment, equating it with the majority, he also praised my brother for standing his ground in the argument: “You did very well against three antagonists. I liked it.”

Then, after making his case against revolution and for incremental change, perhaps in an effort to be conciliatory, he agreed with my brother on one point:

“A president who says he would rather go to a baseball game than to listen to protesters is a fool. Nixon is not the first stupid president. We had Coolidge, before him Harding. So what? The country survived them.” From his lips…

The First Letter of the Alphabet

Tonight my Yiddish group meets again. Yesterday, getting ready and searching for something topical, I thought of the Chanukah song I learned in my childhood, “Oh Channukah, Oh Channukah.” I suddenly understood something I’ve known/not-known for fifty years and never thought about. Children often learn songs as a string of syllables, without any idea of what they are singing. Sometimes, you can sing a song your whole life and never notice that you don’t know what it means. It was an oddly delicious feeling when the line ‘… tsin kinder, di khanike likhtelekh on,” came to me, and I realized I had never known what I was singing, but now I do. Ontsinden is a separable verb that means to kindle, or to light. “Light, children, the Channukah candles up.” Cool.

Only three or four or five people show up to our Yiddish Ithaca meetings these days. I’m told Rome wasn’t built in a day. But on the other hand I don’t want to build Rome. In fact, I just wrote a whole paragraph on Rome, tyranny, and the Jews, and then deleted it. Not building Rome.

One of those regular attendees knows a lot of Yiddish by ear, but never learned to read. I feel bad, because I am essentially leading a reading group. I do not have the chops to lead a conversation group. She announced early that she wanted to stay and listen, but was not going to learn to read. She had tried before, and failed. We worked on her, and reluctantly, she agreed to take it on, to give it one more try. Her stipulation was that she would only learn one letter of the alphabet per meeting.

And she is doing it. I admire someone who knows something will be hard and tries anyway, who knows that she will not reach her ultimate desired destination, but who takes the next step anyway. She will keep me at this even if it ends up being just us. Usually, I bring three or four things to our meetings. We typically get to two of them. Tonight, one of these will be a worksheet for the letter gimel.

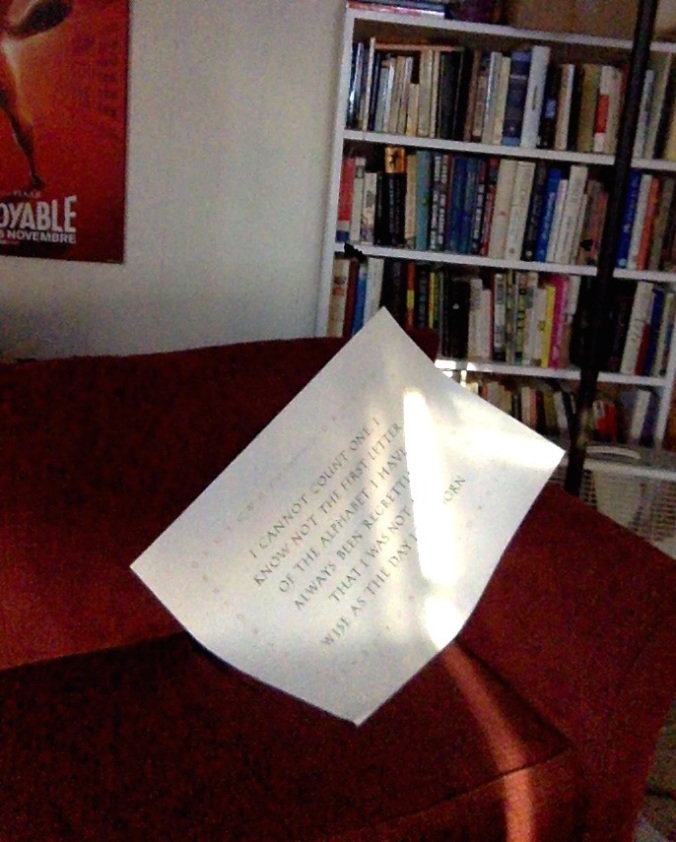

Gimel is already not aleph. The quote with which I started this blogpost, “I cannot count one. I know not the first letter of the alphabet,” is from Walden. It follows Thoreau’s famous ecstatic image of fishing among the stars. Up and down are one. Space and time are meaningless. The infinite can be grasped by reaching out your hand. This is a transcendent experience of being in not-knowing, of breaking through fixed forms and receiving the universe, not mediated through the symbols of mathematics or literacy, but directly. Nevertheless, what brings his vision to us is a work of literature and of craft. Consider me firmly in the pro-alphabet camp.

–

Still life with Walden quote. Sorry I’m without a camera these days. Still a misty-eyed view probably improves Thoreau.